This year’s priority: Acceleration

The African Union’s theme for 2023 is “Year of AfCFTA: Acceleration of AfCFTA Implementation.” And with good reason. A flagship project of the AU, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers an unprecedented opportunity to realize a more integrated and prosperous continent as envisioned in the AU’s Agenda 2063, Africa’s framework for structural transformation.

The AfCFTA is the AU’s principal mechanism for the inclusive and sustainable development of industry, infrastructure, and agriculture on the continent and more intra-African trade. It sits alongside five other initiatives related to integration and development:

- The Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence and Right of Establishment

- The Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa

- The Accelerated Industrial Development for Africa initiative

- The Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Program

- The Single African Air Transport Market

The AfCFTA has its origins in a decision adopted by AU Heads of State in 2012 to establish a continental free trade area that would culminate in a single market for goods and services in which businesspeople and investments may move freely across borders. Negotiations began in 2015 and the AfCFTA Agreement was formally launched three years later, but the Agreement only entered into force nominally on 30 May 2019, when the 22nd instrument of ratification was deposited. More ratifications followed, and over the past year, three more AU member states deposited their instruments of ratification with the AU Secretariat, bringing the total to 47.

Although the AfCFTA entered into force in 2019, its signatories are still negotiating aspects of tariff concessions, rules of origin, and other issues. They acknowledge that preferential trade can only begin in earnest once these matters have been agreed. It is at that point that the AfCFTA will eliminate 97% of tariffs on intra-Africa trade and clear the way for the share of African exports traded within the region to rise beyond its current level, the lowest in the world.

Once the negotiations are complete and the Agreement is fully implemented, the AfCFTA will be the largest free trade agreement in the world, a modern system whose instruments exist alongside pre-existing regional customs unions and trade areas. It will count more member states, cover a larger geographic area, and concern more people than any other trade agreement.

Three phases of implementation

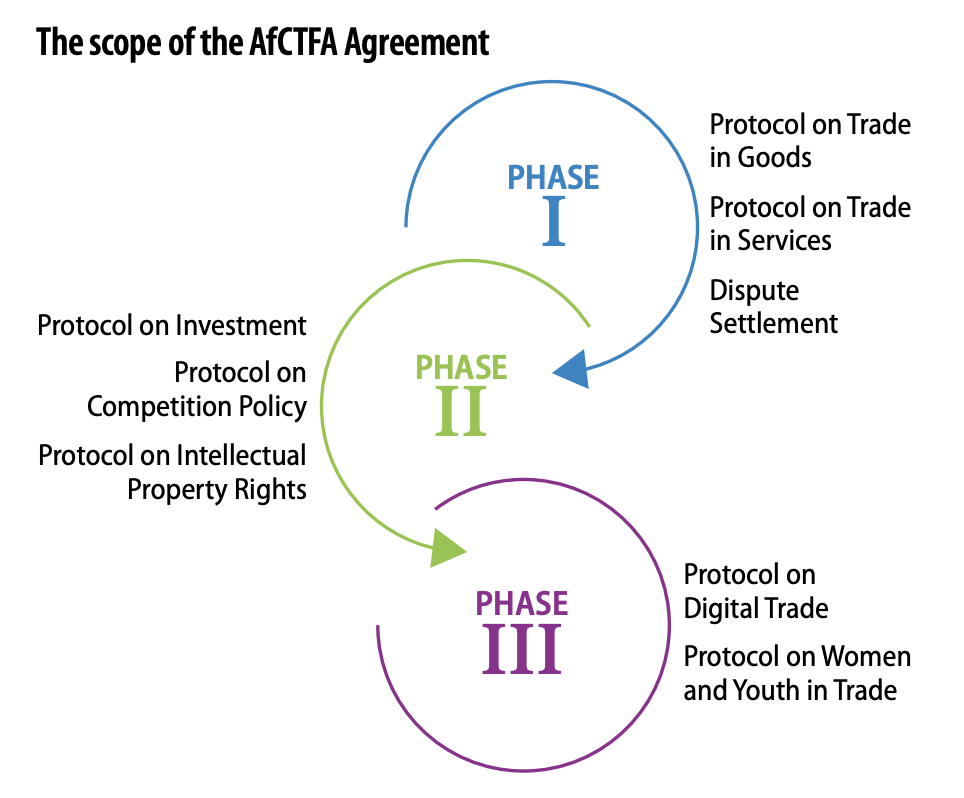

Trade in goods was one of the AfCFTA’s first areas of negotiation: it was considered part of Phase I, alongside trade in services and dispute settlement mechanisms. Protocols on these areas have been agreed, but negotiations continue on the annexes and such matters as rules of origin and schedules of tariff concessions. The negotiations on customs and border management, trade facilitation, and transit arrangements are complete.

Protocols on investment, competition, and intellectual property rights fall under Phase II of the negotiations and have been agreed as well. Some of these matters link to issues covered in Phase 1: foreign direct investment, for example, often links closely to trade in services.

A protocol on digital trade and a protocol on women and youth in trade are being addressed now, as part of Phase III. These two protocols will cover e-commerce, gender-specific barriers to trade, and trade impediments that affect the continent’s youth. Negotiations on these protocols are expected to conclude in 2023.

None of these phases and issues exist in silos. To a large extent, they all link to, depend on, and are enabled by the movement of persons across the continent’s borders.

Trade in services—intertwined with the movement of persons

Trade in services accounts for a substantial share of a country’s GDP and is a key driver of economic growth and job creation. Trade in services is deeply enmeshed with trade in goods and trade facilitation; establishment of a commercial presence (which falls under the Mode 3 category of services—see box below) is in fact foreign direct investment.

Truck drivers, for example, are service providers who act as essential logistical agents for trade in goods but whose efficiency depends on efficient border-crossing systems (customs and immigration), the mutual recognition of standards and certifications (axle weight limits, professional driving permits, and so on), the quality of roads, and the ease with which they can travel.

In sectors other than transport, too, much of the trade in services—and the economic benefits of integration—depends on people being able to move freely across borders: whether to consume or supply a service abroad, or to establish a commercial presence in another country.

Article 4 of the AfCFTA Agreement commits the Agreement’s signatories to progressively liberalize trade in services. Trade in services has its own protocol (alongside the Trade in Goods Protocol under the AfCTFA) and several annexes. Negotiations on the Protocol on Trade in Services are underway and aim to conclude by the end of 2023. For now, commitments are being scheduled in five service sectors: financial services, transportation, business services, communication, and tourism. Future rounds of negotiations will cover other sectors, such as education, construction, and distribution.

The AfCFTA’s agenda on trade in services is an opportunity to accelerate progress in this area and compensate for regional economic communities' (RECs') relatively little headway. Even as negotiations continue, however, the AfCFTA does not prevent countries from negotiating reciprocal commitments in sectors or sub-sectors other than those prioritized in the current negotiations.

Informal cross-border trade and the movement of persons

In many border regions, informal cross-border trade (ICBT) is the lifeblood of communities, creating jobs and contributing to food security. Goods traded informally can be locally produced, like agricultural commodities or manufactured products, or produced on world markets and redistributed through informal but well-organized networks.

By some estimates, ICBT represents between 30% and 72% of all trade between neighbouring African countries, and between 7% and 16% of intra-Africa trade overall. In the absence of a formal definition of ICBT, common differentiators include whether transactions are formally captured by customs authorities (possibly with duties applied) and whether traders are registered.

ICBT has an important gender dimension. Studies show that in some regions, women account for over 70% of small-scale cross-border traders.

Within some RECs, countries are simplifying trade regimes not only to regularize a portion of ICBT, but also to ease the burden on informal traders. They are waiving duties on consignments below a certain threshold or revamping administrative overheads to only apply to formal trade.

To have the most impact, though, trade facilitation measures require an open approach to people crossing borders. Easing border-crossing procedures by doing away with the need for a visa, or re

Update on the Guided Trade Initiative

Given the non-linear progress on the negotiation and adoption of various components of the AfCFTA, in July 2022 the AfCFTA’s Council of Ministers invited countries that had submitted their tariff schedules to begin trading under the AfCFTA. Not only did this create an opportunity for countries that had not previously traded with one another on a preferential basis to conduct commercially meaningful trade for the first time, it also sent a message to countries that had not yet concluded their tariff negotiations: African economic operators are ready to trade under the AfCFTA, and the process won’t wait.

Known as the Guided Trade Initiative (GTI), the trading program applies to eight countries: Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Tunisia. The GTI makes more than 96 products eligible for trade among these countries, with additional products to be added in 2023. To qualify for trading under the GTI, products must be covered by a tariff offer (concession), and criteria for rules of origin have to have been agreed.

Eligible products include ceramic tiles, batteries, horti-culture products, avocados, flowers, pharmaceuticals, palm oil, tea, and rubber.

An initiative similar to the GTI is now planned for trade in services in the AfCFTA’s five priority service sectors: financial services, transportation, business services, communication, and tourism. The modalities of the new trading program are not yet final, but like the GTI for trade in goods, the program will be an interim arrangement that falls away once the Protocol on Trade in Services and its annexes are implemented.

Like the GTI, the success of this program hinges, at least in part, on the free movement of persons between countries.

Progress on rules of origin

For a free trade agreement to function, the parties must agree on several key provisions. One provision concerns tariff offers: the concessions that each country applies to the goods that another country seeks to export to it. Another provision concerns rules of origin: the criteria that determine the economic nationality of a good. Designed to ensure that only goods produced by the parties to a free trade agreement benefit from preferential access under the agreement, rules of origin set out the conditions that products must meet if they are to be considered as having originated in the exporting country. Generally, rules of origin state that the product's inputs must have been wholly obtained in the originating country or—if the product contains imported materials—have been substantially transformed there.

As mentioned in last year’s AVOI report, the rules of origin agreed under the AfCFTA apply to preferential trade between countries not already part of a REC that already operates a preferential trade regime.

Finding the right balance

The design of rules of origin is time-consuming and highly technical. It is also consequential: a region's industries can thrive and new economic activity incentivized, depending on how the rules are designed. Working with countries to agree on a common standard for what constitutes a product “made in Africa” is all the more challenging when countries have different resources, are economically diverse, or are at different stages of development.

Insofar as producers are concerned, restrictive rules of origin impose a higher burden in that they require a larger share of a good’s components to originate on the soil of parties to the preferential trade area. Liberal rules give producers more flexibility: they allow a larger share of inputs to be sourced from third parties—parties located outside the preferential trade area.

A delicate balance is required, one that encourages local industrial activity and incentivizes the development of regional value chains, while recognizing that trade under the AfCFTA will flounder if the region does not produce enough of the inputs, at a competitive price, that African producers need for their exports to qualify for trading under AfCFTA’s preferential terms.

Progress over the last year

Most of the AfCFTA’s rules of origin have now been agreed; the only outstanding rules are in automotive manufacturing and the textiles and clothing sector. These sectors have long been sticking points, not least because countries around the continent are involved in their production chains and have a vested interest in how their rules of origin are designed. It is generally recognized that the rules of origin for these sectors could impact Africa’s industrial development significantly.

The provisions for several tariff lines and product categories in these sectors have now been agreed in principle, and the final negotiations are being conducted through the AfCFTA Council of Ministers responsible for trade. The council has dedicated task teams to advance the negotiations.

Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons in Africa

The Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence and Right of Establishment has been signed by 32 African countries: 30 when the protocol was launched in March 2018 alongside the AfCFTA, and two later. By freeing the movement of Africans throughout Africa, the protocol will facilitate intra-African trade and investment, create and promote employment opportunities, make labour more mobile, and raise living standards.

The protocol will be implemented in three phases. In the first phase, it will liberalize the right of entry; in the second, the right of residence; and in the third, the right of establishment.

Despite a promising beginning, only four countries have ratified the protocol to date: Mali (ranked 28th on the AVOI), Niger (ranked 34th), Rwanda (ranked joint first), and São Tomé and Principe (ranked 45th). Ratification does not correlate with visa openness: Rwanda offers visa-free entry to citizens from all African countries, while São Tomé and Principe still requires the citizens of 46 countries to obtain a visa ahead of travel.

Most of the highest-ranked countries on the AVOI have not signed the protocol. The number of ratifications has not changed in recent years and is well below the threshold of 15 countries needed for the protocol to enter into force.

The slow pace of ratification is likely rooted in concerns about national security, poor or insufficient border management, and perceptions of a loss of control over national migration policy. It might also stem from a misunderstanding of countries’ obligations and the timing of the protocol’s implementation. Domestic political and social narratives also play a role, especially where high unemployment feeds concerns about jobs for nationals, where security issues are prominent, or where civil registry systems and possibilities to exchange information between countries are considered inadequate.

Parallel tracks

The freedom of movement in Africa sometimes progresses more quickly at the regional level than on the continental level. In some RECs, high levels of reciprocal visa-free travel have caused countries to climb the ranks of the AVOI. ECOWAS and EAC operate regional movement protocols, and COMESA is reviving a protocol that was never fully adopted and implemented. SADC has facilitated the movement of people as well, less by means of a regional agreement than by bilateral agreements that leave plenty of room for national sovereignty.

At the country level, too, many countries that have not yet ratified the protocol have made significant strides towards visa openness. Some have introduced innovative ways to ease travel and entry.

Whatever the channel, for free trade in Africa to become a reality, Africans need to be freer to move across the continent. Cross-border investment, the development of regional value chains, and broad-based economic integration all depend on it. Addressing legitimate concerns about the mechanics of the protocol, clarifying the protocol’s roadmap for implementation, and helping countries exchange information more transparently would move free movement forward.

Creating an enabling environment for African value chains

The value and volume of intra-African trade has long lagged the value and volume of trade between Africa and other regions of the world. The nature of trade is different, too. With partners outside the continent, Africa mostly imports finished goods and exports primary goods and extractive materials. This leaves the most lucrative activities in the value chain—the beneficiation of raw materials—profiting parties outside Africa.

The AfCFTA is helping create an alternative to this model. Rules of origin aim to incentivize the use of African inputs in manufacturing and processing. Trade facilitation measures will help streamline intra-African customs. And countries that had long imposed tariffs on each other’s goods are agreeing to remove tariffs on most trade. All of this will encourage economic diversification and intra-African trade.

Part of the AfCFTA’s strategy is to drive the development of regional value chains. More value chains within Africa would create jobs, make production more efficient, raise living standards, and increase food security. Countries would have more reasons to specialize in their areas of comparative advantage, developing greater expertise in downstream beneficiation activities that add more value than extraction and raw production.

These developments can thrive in a fertile environment where the flow of goods and services across borders takes place efficiently and without undue barriers, and where people and skills can move freely.

This year’s priority: Acceleration

The African Union’s theme for 2023 is “Year of AfCFTA: Acceleration of AfCFTA Implementation.” And with good reason. A flagship project of the AU, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers an unprecedented opportunity to realize a more integrated and prosperous continent as envisioned in the AU’s Agenda 2063, Africa’s framework for structural transformation.

The AfCFTA is the AU’s principal mechanism for the inclusive and sustainable development of industry, infrastructure, and agriculture on the continent and more intra-African trade. It sits alongside five other initiatives related to integration and development:

- The Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence and Right of Establishment

- The Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa

- The Accelerated Industrial Development for Africa initiative

- The Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Program

- The Single African Air Transport Market

The AfCFTA has its origins in a decision adopted by AU Heads of State in 2012 to establish a continental free trade area that would culminate in a single market for goods and services in which businesspeople and investments may move freely across borders. Negotiations began in 2015 and the AfCFTA Agreement was formally launched three years later, but the Agreement only entered into force nominally on 30 May 2019, when the 22nd instrument of ratification was deposited. More ratifications followed, and over the past year, three more AU member states deposited their instruments of ratification with the AU Secretariat, bringing the total to 47.

Although the AfCFTA entered into force in 2019, its signatories are still negotiating aspects of tariff concessions, rules of origin, and other issues. They acknowledge that preferential trade can only begin in earnest once these matters have been agreed. It is at that point that the AfCFTA will eliminate 97% of tariffs on intra-Africa trade and clear the way for the share of African exports traded within the region to rise beyond its current level, the lowest in the world.

Once the negotiations are complete and the Agreement is fully implemented, the AfCFTA will be the largest free trade agreement in the world, a modern system whose instruments exist alongside pre-existing regional customs unions and trade areas. It will count more member states, cover a larger geographic area, and concern more people than any other trade agreement.

Three phases of implementation

Trade in goods was one of the AfCFTA’s first areas of negotiation: it was considered part of Phase I, alongside trade in services and dispute settlement mechanisms. Protocols on these areas have been agreed, but negotiations continue on the annexes and such matters as rules of origin and schedules of tariff concessions. The negotiations on customs and border management, trade facilitation, and transit arrangements are complete.

Protocols on investment, competition, and intellectual property rights fall under Phase II of the negotiations and have been agreed as well. Some of these matters link to issues covered in Phase 1: foreign direct investment, for example, often links closely to trade in services.

A protocol on digital trade and a protocol on women and youth in trade are being addressed now, as part of Phase III. These two protocols will cover e-commerce, gender-specific barriers to trade, and trade impediments that affect the continent’s youth. Negotiations on these protocols are expected to conclude in 2023.

None of these phases and issues exist in silos. To a large extent, they all link to, depend on, and are enabled by the movement of persons across the continent’s borders.

Trade in services—intertwined with the movement of persons

Trade in services accounts for a substantial share of a country’s GDP and is a key driver of economic growth and job creation. Trade in services is deeply enmeshed with trade in goods and trade facilitation; establishment of a commercial presence (which falls under the Mode 3 category of services—see box below) is in fact foreign direct investment.

Truck drivers, for example, are service providers who act as essential logistical agents for trade in goods but whose efficiency depends on efficient border-crossing systems (customs and immigration), the mutual recognition of standards and certifications (axle weight limits, professional driving permits, and so on), the quality of roads, and the ease with which they can travel.

Tackling negotiations on trade in services

Phase I of the AfCFTA negotiations concerns trade in goods and services and dispute settlement. The AfCFTA models its negotiations of trade in services on the World Trade Organization’s General Agreement on Trade in Services, which categorizes trade in services in four modes. Modes 2, 3, and 4 depend on the ability of persons to move across borders, either as consumers or as providers of a service.

Mode 1: The cross-border supply of a service from the territory of one country to the territory of another country (e.g., digitally transmitted architectural drawings, consultancy reports sent by email)

Mode 2: Consumption abroad: situations where the citizen of one country moves into the territory

of another country to consume a service there (e.g., tourists or patients who travel abroad for medical care)

Mode 3: The establishment of a commercial presence (such as a branch or subsidiary) by the service supplier of one country in the territory of another country

Mode 4: The provision of a service through the temporary presence of the citizens of one country in the territory of another country (e.g., teachers or engineers working abroad)

In sectors other than transport, too, much of the trade in services—and the economic benefits of integration—depends on people being able to move freely across borders: whether to consume or supply a service abroad, or to establish a commercial presence in another country.

Article 4 of the AfCFTA Agreement commits the Agreement’s signatories to progressively liberalize trade in services. Trade in services has its own protocol (alongside the Trade in Goods Protocol under the AfCTFA) and several annexes. Negotiations on the Protocol on Trade in Services are underway and aim to conclude by the end of 2023. For now, commitments are being scheduled in five service sectors: financial services, transportation, business services, communication, and tourism. Future rounds of negotiations will cover other sectors, such as education, construction, and distribution.

The AfCFTA’s agenda on trade in services is an opportunity to accelerate progress in this area and compensate for regional economic communities' (RECs') relatively little headway. Even as negotiations continue, however, the AfCFTA does not prevent countries from negotiating reciprocal commitments in sectors or sub-sectors other than those prioritized in the current negotiations.

Informal cross-border trade and the movement of persons

In many border regions, informal cross-border trade (ICBT) is the lifeblood of communities, creating jobs and contributing to food security. Goods traded informally can be locally produced, like agricultural commodities or manufactured products, or produced on world markets and redistributed through informal but well-organized networks.

By some estimates, ICBT represents between 30% and 72% of all trade between neighbouring African countries, and between 7% and 16% of intra-Africa trade overall. In the absence of a formal definition of ICBT, common differentiators include whether transactions are formally captured by customs authorities (possibly with duties applied) and whether traders are registered.

ICBT has an important gender dimension. Studies show that in some regions, women account for over 70% of small-scale cross-border traders.

Within some RECs, countries are simplifying trade regimes not only to regularize a portion of ICBT, but also to ease the burden on informal traders. They are waiving duties on consignments below a certain threshold or revamping administrative overheads to only apply to formal trade.

To have the most impact, though, trade facilitation measures require an open approach to people crossing borders. Easing border-crossing procedures by doing away with the need for a visa, or re

Update on the Guided Trade Initiative

Given the non-linear progress on the negotiation and adoption of various components of the AfCFTA, in July 2022 the AfCFTA’s Council of Ministers invited countries that had submitted their tariff schedules to begin trading under the AfCFTA. Not only did this create an opportunity for countries that had not previously traded with one another on a preferential basis to conduct commercially meaningful trade for the first time, it also sent a message to countries that had not yet concluded their tariff negotiations: African economic operators are ready to trade under the AfCFTA, and the process won’t wait.

Known as the Guided Trade Initiative (GTI), the trading program applies to eight countries: Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Tunisia. The GTI makes more than 96 products eligible for trade among these countries, with additional products to be added in 2023. To qualify for trading under the GTI, products must be covered by a tariff offer (concession), and criteria for rules of origin have to have been agreed.

Eligible products include ceramic tiles, batteries, horti-culture products, avocados, flowers, pharmaceuticals, palm oil, tea, and rubber.

An initiative similar to the GTI is now planned for trade in services in the AfCFTA’s five priority service sectors: financial services, transportation, business services, communication, and tourism. The modalities of the new trading program are not yet final, but like the GTI for trade in goods, the program will be an interim arrangement that falls away once the Protocol on Trade in Services and its annexes are implemented.

Like the GTI, the success of this program hinges, at least in part, on the free movement of persons between countries.

Progress on rules of origin

For a free trade agreement to function, the parties must agree on several key provisions. One provision concerns tariff offers: the concessions that each country applies to the goods that another country seeks to export to it. Another provision concerns rules of origin: the criteria that determine the economic nationality of a good. Designed to ensure that only goods produced by the parties to a free trade agreement benefit from preferential access under the agreement, rules of origin set out the conditions that products must meet if they are to be considered as having originated in the exporting country. Generally, rules of origin state that the product's inputs must have been wholly obtained in the originating country or—if the product contains imported materials—have been substantially transformed there.

As mentioned in last year’s AVOI report, the rules of origin agreed under the AfCFTA apply to preferential trade between countries not already part of a REC that already operates a preferential trade regime.

Finding the right balance

The design of rules of origin is time-consuming and highly technical. It is also consequential: a region's industries can thrive and new economic activity incentivized, depending on how the rules are designed. Working with countries to agree on a common standard for what constitutes a product “made in Africa” is all the more challenging when countries have different resources, are economically diverse, or are at different stages of development.

Insofar as producers are concerned, restrictive rules of origin impose a higher burden in that they require a larger share of a good’s components to originate on the soil of parties to the preferential trade area. Liberal rules give producers more flexibility: they allow a larger share of inputs to be sourced from third parties—parties located outside the preferential trade area.

A delicate balance is required, one that encourages local industrial activity and incentivizes the development of regional value chains, while recognizing that trade under the AfCFTA will flounder if the region does not produce enough of the inputs, at a competitive price, that African producers need for their exports to qualify for trading under AfCFTA’s preferential terms.

Progress over the last year

Most of the AfCFTA’s rules of origin have now been agreed; the only outstanding rules are in automotive manufacturing and the textiles and clothing sector. These sectors have long been sticking points, not least because countries around the continent are involved in their production chains and have a vested interest in how their rules of origin are designed. It is generally recognized that the rules of origin for these sectors could impact Africa’s industrial development significantly.

The provisions for several tariff lines and product categories in these sectors have now been agreed in principle, and the final negotiations are being conducted through the AfCFTA Council of Ministers responsible for trade. The council has dedicated task teams to advance the negotiations.

Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons in Africa

The Protocol on the Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence and Right of Establishment has been signed by 32 African countries: 30 when the protocol was launched in March 2018 alongside the AfCFTA, and two later. By freeing the movement of Africans throughout Africa, the protocol will facilitate intra-African trade and investment, create and promote employment opportunities, make labour more mobile, and raise living standards.

The protocol will be implemented in three phases. In the first phase, it will liberalize the right of entry; in the second, the right of residence; and in the third, the right of establishment.

Despite a promising beginning, only four countries have ratified the protocol to date: Mali (ranked 28th on the AVOI), Niger (ranked 34th), Rwanda (ranked joint first), and São Tomé and Principe (ranked 45th). Ratification does not correlate with visa openness: Rwanda offers visa-free entry to citizens from all African countries, while São Tomé and Principe still requires the citizens of 46 countries to obtain a visa ahead of travel.

Most of the highest-ranked countries on the AVOI have not signed the protocol. The number of ratifications has not changed in recent years and is well below the threshold of 15 countries needed for the protocol to enter into force.

The slow pace of ratification is likely rooted in concerns about national security, poor or insufficient border management, and perceptions of a loss of control over national migration policy. It might also stem from a misunderstanding of countries’ obligations and the timing of the protocol’s implementation. Domestic political and social narratives also play a role, especially where high unemployment feeds concerns about jobs for nationals, where security issues are prominent, or where civil registry systems and possibilities to exchange information between countries are considered inadequate.

Parallel tracks

The freedom of movement in Africa sometimes progresses more quickly at the regional level than on the continental level. In some RECs, high levels of reciprocal visa-free travel have caused countries to climb the ranks of the AVOI. ECOWAS and EAC operate regional movement protocols, and COMESA is reviving a protocol that was never fully adopted and implemented. SADC has facilitated the movement of people as well, less by means of a regional agreement than by bilateral agreements that leave plenty of room for national sovereignty.

At the country level, too, many countries that have not yet ratified the protocol have made significant strides towards visa openness. Some have introduced innovative ways to ease travel and entry.

Whatever the channel, for free trade in Africa to become a reality, Africans need to be freer to move across the continent. Cross-border investment, the development of regional value chains, and broad-based economic integration all depend on it. Addressing legitimate concerns about the mechanics of the protocol, clarifying the protocol’s roadmap for implementation, and helping countries exchange information more transparently would move free movement forward.

Creating an enabling environment for African value chains

The value and volume of intra-African trade has long lagged the value and volume of trade between Africa and other regions of the world. The nature of trade is different, too. With partners outside the continent, Africa mostly imports finished goods and exports primary goods and extractive materials. This leaves the most lucrative activities in the value chain—the beneficiation of raw materials—profiting parties outside Africa.

The AfCFTA is helping create an alternative to this model. Rules of origin aim to incentivize the use of African inputs in manufacturing and processing. Trade facilitation measures will help streamline intra-African customs. And countries that had long imposed tariffs on each other’s goods are agreeing to remove tariffs on most trade. All of this will encourage economic diversification and intra-African trade.

Part of the AfCFTA’s strategy is to drive the development of regional value chains. More value chains within Africa would create jobs, make production more efficient, raise living standards, and increase food security. Countries would have more reasons to specialize in their areas of comparative advantage, developing greater expertise in downstream beneficiation activities that add more value than extraction and raw production.

These developments can thrive in a fertile environment where the flow of goods and services across borders takes place efficiently and without undue barriers, and where people and skills can move freely.